We are not practicing Continuous Delivery. I know this because Jez Humble has given a very clear test. If you are not checking your code into trunk at least once every day, says Jez, you are not doing Continuous Integration, and that is a prerequisite for Continuous Delivery. I don’t do this; no one on my team does it; no one is likely to do it any time soon, except by an accident of fortuitous timing. Nevertheless, his book is one of the most useful books on software development I have read. We have used it as a playbook for improvement, with the result being highly effective software delivery. Our experience is one small example of an interesting historical process, which I’d like to sketch in somewhat theoretical terms. Software is a psychologically intimate technology. Much as described by Gilbert Simondon’s work on technical objects, building software has evolved from a distractingly abstract high modernist endeavour to something more dynamic, concrete and useful.

The term software was co-opted, in a computing context, around 1953, and had time to grow only into an awkward adolescence before being declared, fifteen years later, as in crisis. Barely had we become aware of software’s existence before we found it to be a frightening, unmanageable thing, upsetting our expected future of faster rockets and neatly ordered suburbs. Many have noted that informational artifacts have storage and manufacturing costs approaching zero. I remember David Carrington, in one of my first university classes on computing, noting that as a consequence of this, software maintenance is fundamentally a misnomer. What we speak of as maintenance in physical artifacts, the replacement of entropy-afflicted parts with equivalents within the same design, is a nonsense in software. The closest analogue might be system administrative activities like bouncing processes and archiving logfiles. What we call (or once called) maintenance is revising our understanding of the problem space.

Software has an elastic fragility to it, pliable, yet prone to the discontinuities and unsympathetic precision of logic. Lacking an intuition of digital inertia, we want to change programs about as often as we change our minds, and get frustrated when we cannot. In their book Continuous Delivery, Humble and Farley say we can change programs like that, or at least be changing live software very many times a day, such that software development is not the bottleneck in product development.

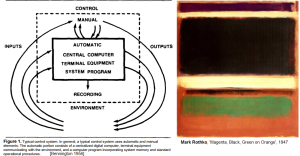

With this approach, we see a rotation and miniaturisation of mid-twentieth century models of software development. The waterfall is turned on its side.