George Saunders has written a great sentimental inhumanist novel. The book comes at you time-sorted and many-voiced, like the chat room history of channel #civilwargraveyard. In Lincoln in the Bardo, messages come in slices, and names come uncapitalized, like a child’s signature, or a Twitter handle. Even the blocks of interspersed historical (or pretend-historical) text that ground the story have the feel of a link followed, or a long block quote shared as a photo, as those on bookish corners of the platform might recognize.

Amy Ireland has the best description, from 2016, of the sliced up, liminal design affordances of the birdsite, and so this novel:

Twitter is excellent. The botlife runs wild and free, swerving into sheer paranoia-inducing bizarreness at times (Weird Sun Twitter) and there are writers doing really innovative work that engages directly with the unique formal possibilities of the medium (Uel Aramchek’s ‘This Could Be Your Past’ is one of my favourite recent examples). It’s the Arcadia of human/bot collaboration.

[…]

Only here we have a scroll updated to capitalise on the possibilities of hypertextuality: it is effectively nonlinear yet accommodates series of interlinked tweets, its citation system harbours abyssal potential for embedded referencing, its search function and the public nature of its contents make for a vast and bizarre dataset […], and it forces the honing of expression to a compact 140 characters Per unit of information. […]

During its first exciting moments, Twitter appears as an open horizon for the accumulation of all sorts of gratifying information, […] Nevertheless, the illusion of accumulation inevitably breaks down and it does so in perfect correspondence with the intensity of one’s Twitter habit. Accumulation cycles pathologically into dispersion, and before you recognise what is occurring, the mesmeric infinity of the digital scroll has entirely voided your capacity to focus or reflect. There is nowhere to go but further into the abyss.

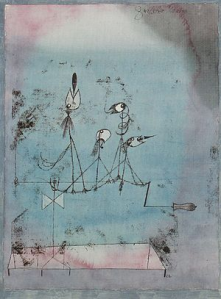

If one could allot a genre to the platform as a whole, Twitter would be horror. The interface manifests visually and cognitively as a series of incisions. What begins as a benign mode of textual organisation quickly becomes applicable to human concentration. Its twentieth century prototype can perhaps be found in the mechanical writing/torture machine of Kafka’s In the Penal Colony. Both oversee the virulent machining of the human through text, and both tend towards a similar outcome in which the relentless numerical insistence of machinic agency ultimately succeeds in eradicating the latter.

– Poetry is Cosmic War, AJ Carruthers interview with Amy Ireland

The bardo is an intermediate state between death and rebirth in Tibetan Buddhism, a purgatorial place where we are separated from ties to mortal lives. So the Bardo Thodol, the Tibetan Book of the Dead, is more literally translated Liberation Through Hearing In The Intermediate State. Saunders populates the bardo with ghosts, imprisoned within the frame of a Washington graveyard, lost in scripts of their former lives, niggling at their traumas without accepting the central fact that they are dead.

The story follows the ghost of the boy Willie Lincoln, and the imagined aftermath of his sad death of typhoid at eleven years old. Eleven years old, that transitional age; “A sunny child, dear & direct, abundantly open to the charms of the world.” The talking, however, is largely done by more experienced graveyard spirits. There are quite a number – slave women and plantation owners, soldiers and farmwives – but with three men foregrounded: Hans Vollman, Roger Bevins III, and the Reverend Everly Thomas. Now with ghosts, Buddhism, death, presidents, Christianity, the US civil war, and what not, there’s a vast swathe of cultural allusions you could be drawing from. But I found myself most reminded of Journey To The West 西游记.

Delving into spoilery detail, three imprisoned spirits become disciples to a younger mortal, after a bit of ear-boxing encouragement at the start. Following his teachings and example, they protect him on his long journey, saving him from many demons intent on eating his flesh. Though they possess great magical power, when they get really stuck they need to call on Guanyin 观音, the bodhisattva goddess of mercy, to tip the scales a bit in their favour, and in the end they are released to positions of worth and enlightenment. In this mapping, Willie Lincoln is the monk Xuanzang 玄奘 (Tripitaka), another real historical figure. The three disciples represent different virtues and sins. The Reverend Everly Thomas is the devout and overserious Sandy 沙悟净. Roger Bevins III is Pigsy Eight-sins 猪八戒, consumed by earthly gluttony and lusts, immersed in senses, always growing new eyes, ears and noses. Hans Vollman is the Monkey King 孙悟空, with a more than usually explicitly phallic giant red staff. ((You can even link the names – Vollman – Full Man – 悟空 – 无空 / Without Space, though I’m not sure if anyone really puns in three languages outside Hong Kong.))

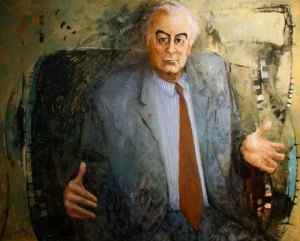

Which makes Abraham Lincoln Guanyin. The One Who Perceives The Sounds of The World. Lincoln, in this mythic shape, is too large to fit onstage for long. We see his shaking grief through the eyes of the spirits, and then he leaves. He is the only character who re-enters and re-exits the graveyard. The Goddess of Mercy. The Great Emancipator.

Of course Lincoln was not just the rail splitter and the breaker of slavechains. He’s also the Doctor Frankenstein of the American body politic, stitching the dismembered states together for reanimation. Both George Saunders and Amy Ireland talk of writing as sampling and reassembling snippets from overwhelming torrents of data. Saunders describes it as curation: “I’d be in my room for six or seven hours, cutting up bits of paper with quotes and arranging them on the floor”, he tells Zadie Smith. Ireland notes that “the diminishment of human authorship plunges the human reader into a problematics of scale. … In response, less linear and sedentary methods of reading start to take precedence – techniques akin to scanning, scrolling, and – for the unashamedly hyperstimulated – spritzing.” In assembling his novel, Saunders does this for us across the corpus of civil war history, Lincoln biography, Sino-Tibetan Buddhism and his own imagination. Yet it still shows the zigzag path across that vast field more honestly and artfully than most novels. The omniscient narrator is replaced with the hyperstimulated archaeologist of the past-saturated present, asynchronously replayed by the reader at a rate just slow enough to allow understanding.

Lincoln’s mutated industrial union doesn’t fit in the novel’s timeline. The reader and the characters are severed from it by a bullet and the matterlightblooming phenomenon of a bound book’s last page. The sensory systems of the brain cut down, sample, pre-processes, and outright alter everything we see and hear. Our machines and our spirits do the same. There’s too much data for human consciousness to comprehend. Wasn’t there always?