Catherynne M. Valente – The Past is Red

EVERY MORNING I wake up to find words painted on my door like toadstools popping up in the night. Today it says NIHILIST in big black letters. That’s not so bad! It’s almost sweet! Big Bargains flumps toward me on her fat seal-belly while I light the wicks on my beeswax door, and we watch them burn together until the word melts away. “I don’t think I’m a nihilist, Big Bargains. Do you?”

She rolls over onto my matchbox stash so that I’ll rub her stomach. Rubbing a seal’s stomach is the opposite of nihilism.

The Past is Red starts with a beautifully direct voice. It’s a young woman’s voice, talking to us in first person, and she’ll be with us for the entire novel, for it’s her story. Tetley, her name is, named after a label on a discarded teabag, and it’s a voice of survivor optimism, the voice of someone finding beauty every day in between episodes of horrible abuse. Tetley is amazing, she finds beauty in garbage, and she lives on a giant floating island of garbage, cobbled together from the future version of the Pacific Garbage Patch. It’s called Garbagetown.

Tetley’s people live on and in Garbagetown because there’s nothing else left after catastrophic climate change. Just garbage and old ships floating atop a world-sized ocean. The rubbish is a serious resource, pragmatically sifted by the residents. They make use of what their predecessors, the Fuckwits – that is, us – threw away. Like the residents of Smokey Mountain, the Manila garbage dump, they have rituals, songs, etiquette, dialects, fashion and social hierarchy. They have a culture.

Tetley is Cinderella, Rapunzel, Cassandra, and a terrorist. The fairy tales come together in a weave that is itself a new fairy tale, not just the execution of a template. As the story progresses, and we learn about the world, Tetley’s moral and intuitive understanding of the world is repeatedly confirmed. This isn’t really a surprise: she’s the hero.

There is something nihilistic and death-loving about this book. It’s not at all lack of craft: it is beautifully written. It’s not abused, romantic Tetley either. Valente writes she knew this story had a special voice from the first sentence, and I believe that. No, the choice that makes this death-loving is the construction of the world.

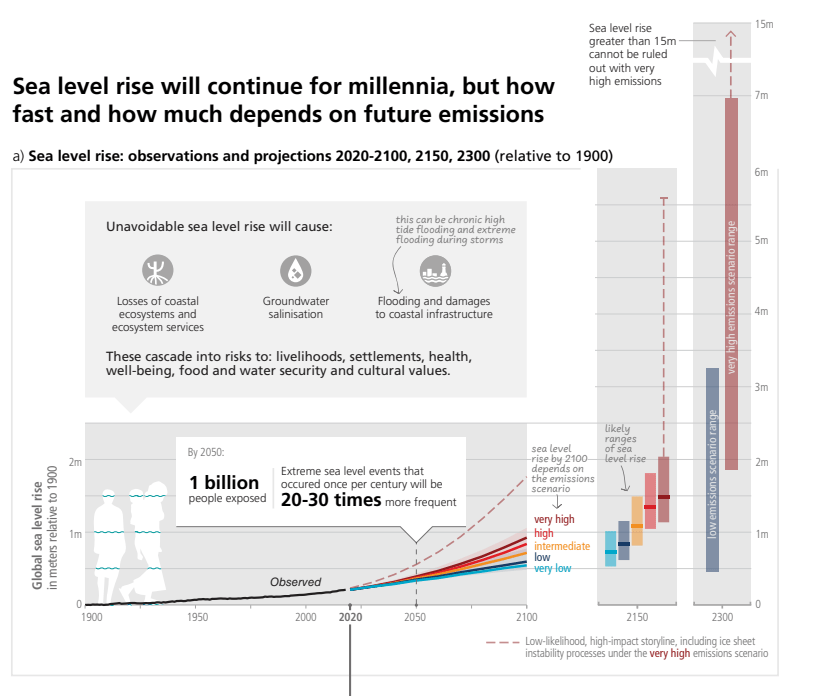

To touch on spoilers, it is an ocean world not just in the sense that the oceans rose and coastal cities were destroyed. In this book everything terrestrial is now underwater – everything except a sad little island a few hundred metres wide, full of memorials. This is also a nearish future setting, where various bits of historical electronics still work, if well maintained and you get lucky. Now, a common very high emission scenario – a scenario where we go backwards on the lukewarm carbon emission progress made since the nineties – has a projected sea level rise of seven metres by the year 2300. Let’s be clear – seven metres is pretty catastrophic. It would flood cities and displace millions or even a billion people. But there’s a hill at the end of my street that’s about fifty metres tall. I live in Brisbane, on the coast, too. Drive 130 km west to Toowoomba and you can get a whole regional city at 690 metres elevation, on the flattest continent on Earth. Even Singapore, a small, flat island hugely vulnerable to sea rise caused by climate change, has Bukit Timah hill, 164 metres tall. The standard science could be wrong by an order of magnitude and bits of Singapore would still be well above the water. Actual serious mountain ranges like the Andes or Himalayas are thousands of metres tall; Everest is over eight kilometres.

Obviously Valente is writing fiction and is allowed to make things up. The question is why. Why make a world where there is no land, and the humans left need to live only on islands of floating garbage from the before-times? The moral arrow of the story points to an explanation. The virtue of a floating world with no land is that it’s a closed system. We have to learn to make do with what we have. This world of hyper-degrowth and hyper-austerity is beyond even sustainability. Trees can’t come back to replace ship hulls; sails can’t be replaced with canvas from newly grown cotton. Humanity can feed itself fine with seafood, but as the foundations of Garbagetown rot away, in ten or twenty generations of eking out a living, presumably everyone just falls into the sea and dies. This is why Tetley blows up part of Garbagetown – because they were about to waste resources on a futile quest for land, and she is angry that they won’t just conserve and appreciate the beautiful things they have (and then later die). Within the world of the book, she’s totally right. Her reasoning is not from any systematically collected evidence or theory: it’s pure intuition. Or since she was completely right, perhaps we should call it prophecy.

This book was a pick for the Solarpunk reading group, and I see why: Hugo nominee, optimistic protagonist. But it’s actually the most anti-solarpunk novel ever written. There is no hope of building a future of beautiful architecture and technology which supports the harmonious thriving of ecosystems and human societies, even on the other side of catastrophe. It’s an entire society with terminal cancer, and the best they can do is die with grace.

The book’s surface layer is one of tough minded gutter realism, of facing up to tough facts. But this is not at all the planet we ourselves live on. Our planet is not a terminal patient on a cancer ward: it’s a patient in an emergency room. It needs urgent interventions like shutting off coal plants and solar geoengineering, while longer term medicine like changes to healthier lifestyles, energy and social systems, and nurturing of ecosystems back to health, can start to take effect.

Both Tetley’s optimism and her instinctive thriftiness are survivor instincts. She has been compared to Candide, but she reminds me more of survivors of death camps that hoard every scrap they can find. Valente’s fairy tale projects that grief and trauma onto us. The world is just what it is, the fight is already lost, and the best you can do is live quietly and find the beauty in garbage. It’s beautifully crafted. It’s planetary trauma porn. It’s awful.